Eurofighter in service with Germany's Luftwaffe

Part 1: From project to production

Let’s go back in time for about half a century, as we write the year 1977. Fleetwood Mac brings out their epic Rumours album. Star Wars Episode IV runs in the cinemas. The same year would also see West-German, British and French defence ministers to express interest in a joint tactical fighter aircraft programme. An earlier cross-border project had already resulted in the Panavia MRCA Tornado, its first prototype having flown three years prior to this 1977 meeting. These fighter-bombers were destined to replace large numbers of Lockheed F-104G Starfighters. Also, the German/French Alpha Jet was close to entering service, and although the Luftwaffe’s McDonnell-Douglas F-4F Phantom IIs were still quite new, a study for future replacement was tentatively started.

Text: Emiel Sloot

Photos: Emiel Sloot (unless stated otherwise)

Last updated: 22 November 2025

From TKF 90 to EFA

So talks between the above mentioned nations had started. Nevertheless, differences in individual requirements and timelines regarding this new aircraft soon led to the suspension of discussions at government level between the three mentioned countries. At the same time, their respective aviation industries continued to cooperate. Regarding West-Germany, MBB had pitched some ideas, resulting in the TKF 90 (Taktisches Kampfflugzeug 90) project, a delta-winged multi-role aircraft with canards presented in 1978. The British had meanwhile issued various Air Staff Target (AST) requirements for replacement of their Jaguars and Harriers. In 1979, a design quite similar to TKF 90 but with double fins would form the basis of the British-German ECF (European Collaborative Fighter), later redesignated ECA (European Combat Aircraft). However, two years later, the UK would ditch the AST 403 requirement, leaving the whole project as a private venture, without direct state funding. Also, the French had already started to show less interest since they were prevented to become the leaders in the design process.

In 1982, ECA evolved into ACA (Agile Combat Aircraft) and Italy was now eager to join the table, resulting in a project basically run by the same three countries that now had successfully introduced the Tornado. To step things up, it was decided to construct two technology demonstrators based on the ACA requirements. Known as the EAP (Experimental Aircraft Programme), two aircraft would be built and tested by the UK and West Germany, respectively. The contract for the British EAP was signed by their Ministry of Defence on 26 May 1983. But then, the West German MoD rejected to do the same, forcing MBB to largely withdraw from the project and basically terminating the ACA project altogether. It would not be the only occasion that German political unwillingness and hesitation towards both this project and the resulting Eurofighter would negatively effect its development and operational service.

It did not stop British Aerospace to continue with EAP, with 15 percent funded by Italy while MBB retained a one-percent stake to keep at least a minimal connection to the programme. To cut costs, BAe used several Tornado parts to built the single EAP demonstrator such as the rear fuselage and fin. It would even be powered by a set of RB199s, Tornado’s turbofans.

While MBB now lacked governmental support in this project, it wasn’t completely dead in the water. In 1984, they had started a cooperation with Rockwell in view of the X-31 Enhanced Fighter Manoeuvrability demonstrator. This was loosely based on the TKF 90 concept.

Aside the industry’s initiatives, five European countries being West Germany, the UK, France, Italy and now also Spain, still pursued the development of a new fighter aircraft during the mid-1980s, a project now dubbed ‘Jäger 90’ in West Germany. Of course, to get that many nations with ditto wishes aligned is quite the challenge. France would soon share their demands, de facto wanting full control over the design process as well as the test and initial development. In other words, they wanted a European-funded fighter that would become their own Rafale in the end. Not surprisingly, this sparked quite some opposition from the rest, particularly the UK. Despite slightly downgrading their demands, France eventually left the programme by 1985. This would clear the way for the Turin Agreement signed on 1 August 1985 for the new European Fighter Aircraft, or EFA as the programme was now called. Total production was foreseen for no less than 760 aircraft: West Germany and UK wanting 250 each, Italy requiring 160 to replace their ageing Starfighter fleet, and Spain looking for 100 aircraft. The development and production work-share was evenly shared. Although not named as such just yet, Eurofighter was born.

EAP takes off

On 8 August 1986, the EAP demonstrator made its first flight. Having an overall appearance that would not be that different from the later Eurofighter, EAP’s test programme collected a lot of valuable date for the EFA programme. The experimental aircraft featured a digital fly-by-wire flight control system; a basic, early variant of direct-voice-input (DVI); and of course digital cockpit instruments. The various systems were highly integrated to minimize pilot workload, and the avionics architecture was designed to allow the swift addition of new features. Radar and weapons were omitted, as these particular systems were not defined as a goal to be achieved just yet. The EAP’s longitudinal instability resulted in an extremely agile aircraft. Up until the demonstrator’s flying programme was terminated on 1 May 1991, it had accumulated 259 flights by various pilots who were all extremely impressed by its performance and ease to fly.

Back to EFA. Each participating country had expressed their set of requirements, laid down during the definition phase. To coordinate the various industries involved, Eurofighter Jagdflugzeug GmbH was established in West Germany by the end of 1986. And, with the programme barely underway, West Germany was already looking for a way to cut costs. Their Defence Minister Manfred Wörner targeted the research & development part for this. He went even further as he started to seriously consider EFA alternatives. To no avail though: on 23 November 1988 a contract was signed for the full-scale development phase, with a first flight foreseen for 1992. This was already slightly later in view of earlier intentions, but it would still be in time to display the prototype for the Farnborough 1992 Airshow.

Engine and radar disputes

Contract or not: more discussions soon popped up between Germany and the other partners, this time focusing on the engines and radar to equip EFA.

The future fighter was destined to be fitted with new EJ200 engines. As these modern turbofans were still in the development phase, the first set of aircraft would use adapted RB199 engines. As soon as EJ200s would become available, this initial batch of aircraft should be retrofitted with the new power plants. Despite West Germany being already a RB199 user, for some reason they favoured the General Electric F404 for use as an interim solution. Oddly, the Luftwaffe did not operate any aircraft powered by F404s. Spain, with their fleet of EF-18 Hornets, actually did, but they had in fact no objection to use RB199s despite not having Tornados. Anyway, eventually the Germans gave up their resistance and the plan for F404s was dropped.

The radar issue was a similar story. For use in EFA, a new modern and powerful European radar would be developed, however West Germany was keen to adopt the Hughes AN/APG-65. Not by coincidence, since this was the same radar system adopted for the Luftwaffe’s F-4F KWS (Kampfwertsteigerung) a.k.a. ICE (Improved Combat Efficiency) upgrade. Since the new-to-be-developed European radar was meant to be superior to this system, including beyond-visual-range (BVR) capability, especially the British project partner did not go along. In addition, applying a US radar system could negatively effect possible oversees sales, since American approval would be required in that case. As with the engine discussion, West Germany dropped their opposition at some point. In the end, the Eurofighter radar saga proved to be a lengthly one, but more on that in the systems section of our article.

As per work-share agreement, Germany would become responsible in the development of the flight control system, with MBB (later DASA) having gained experience with a modified F-104CCV testbed. At a later stage, BAe and GEC Marconi would step in with their EAP experience, solving some persisting software glitches. In hindsight, with EAP already closely resembling EFA, adoption of EAP’s flight control system fine-tuned for use in EFA could have been a quicker, cheaper and better solution. Guess that’s a price to be paid for such large and complex multinational projects.

More delay

Meanwhile, we have arrived in the early 1990s. The world’s geopolitical situation had changed significantly, with the so-called Iron Curtain now rolled aside.

Construction of the seven development aircraft was now underway, all built for testing in various allocated fields of the programme. However, in 1992, more trouble appeared on the German horizon for Eurofighter 2000, as the aircraft was now being referred to. The reunification of East and West Germany in 1990 turned out to be a costly affair to say the least, and amongst others, large defence projects were easy targets to cut costs. In addition, the aforementioned end of the Cold War and the subsequent disappearance – for now – of nearby military tension created a wide sentiment for disarmament. This certainly had a negative effect on the Eurofighter 2000 programme. In addition, Defence Minister Volker Rühe framing this aircraft as a Cold War product which would be of limited use in the new era, was certainly not helpful. In fact, Rühe tried to downsize or even withdraw from the EF 2000 project on several occasions. Since various alternatives like acquiring off-the-shelf products, or completely redesigning the programme to some sort of EF-light, all turned out to be financially unattractive, Germany remained committed to the programme, although with great grudge.

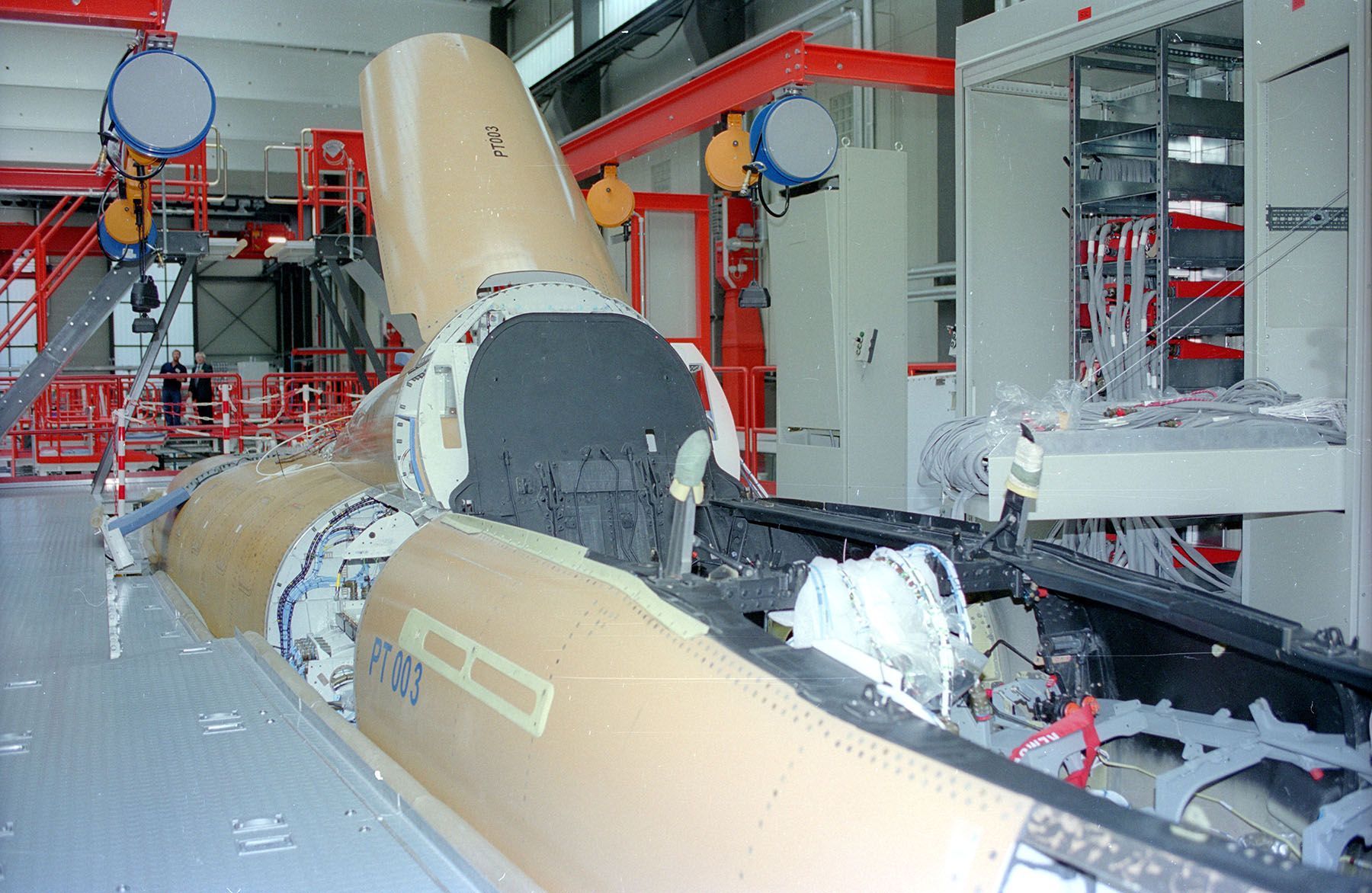

Despite their aversion to the programme, Germany was awarded the honour to have the first flying testbed, being DA1. Built by DASA in Ottobrunn, the aircraft transferred to Manching by road on 11 May 1992 to start a series of ground testing, including engine runs. An in-service date of 1997 for the new fighter still seemed possible, despite some flight control issues yet to be solved.

Eurofighter gets airborne

Still, Germany attempted to cut costs by suggesting several alternative options, including the use of second-hand 27mm cannons, simplifying the design including a single-engined variant, and even to cancel some key systems such as the Defensive Aid Sub-System (DASS). This discussion did result in the eventual design having some systems that customers can opt out. German Eurofighters lacking the PIRATE infrared search and tracking system (see systems section for more details) is a direct result.

With Saab and Lockheed in the process of developing their own new fighters, both encountered serious issues related to the flight control software for the Gripen and YF-22, respectively. On the internet, one can find the videos recorded on accidents with their prototypes in 1989 and 1993 (Gripen) and 1992 (YF-22). Determined to prevent a similar accident, the Eurofighter flight control software was carefully examined before the go for the first flight would be given for DA1, which had been present at Manching since May 1992. But, with the final issues now solved, it took to the skies for the first time on 27 March 1994, serialled 98+29 and flown by test pilot Peter Weger. Although a major milestone for the programme, the event was rather low-key, and the absence of Defence Minister Rühe on this occasion was exemplary if not embarrassing. The time- and funds-consuming search for alternatives made not much difference to the design, but it did mean more delays, with the initial in-service date now slipping beyond 2000.

Development Aircraft

In total, seven so-called Development Aircraft would be produced by the four participating countries, all involved in different aspects in order to get Eurofighter ready for production and cleared for operational use. Focusing on the two built by Germany, DA1 (serialled 98+29) was used for handling and flight control system software development and testing by DASA. Initially fitted with RB199-104D (D for deleted thrust reverser) engines, it received a pair EJ200-03Z turbofans in 1996, and during 1997 it temporarily relocated to BAe Warton for supersonic trials. From April 2003, trials continued at Getafe, Spain by EADS-CASA since their testbed DA6 had been lost in 2002. While in Spain, DA1 also was involved in IRIS-T test-flights, first flying with these missiles on 27 August 2003. A few months later, on 2 December to be exact, DA1 flew with a pair of GBU-10 Paveway II laser-guided 2,000lb bombs. DA1 was retired from service on 21 December 2005, after logging almost 500 flying hours in 578 flights. Fortunately, the mother-of-all-Eurofighters can still be viewed, as 98+29 is preserved at the Flugwerft Schleissheim as part of the Deutsches Museum.

Powered by production-standard EJ200-03A engines, DA5 (serialled 98+30) first flew from Manching on 24 February 1997. This airframe became involved in testing avionics and the Captor radar formerly known as ECR 90, and as such it became the first Eurofighter being fitted with the new radar. It flew with the new CAESAR antenna in May 2007. Later that year, DA5 received extended wing roots or so-called APEX strakes to enhance manoeuvrability (first flight with these on 13 September 2007). Wind-tunnel tests had demonstrated this improvement, especially with higher angle-of-attacks during low speed. The APEX strakes were supposed to be introduced from Block 10 production aircraft and designed to be added quite easily to the existing structure. However, this modification was apparently not adapted after all. Fun Fact: DA5 was the only German Eurofighter with a fake cockpit painted on the underside.

The strake tests were the last test programme for DA5 to be involved. Like its sister ship, DA5 was preserved after it was permanently withdrawn from the test programme in October 2007. In 2010, it was transported by road to be displayed at ILA 2010, with fake serial 31+30. For over a decade, it was on display at the General Steinhoff Kaserne at Berlin-Gatow until it was replaced by retired early production example. DA5 is now stored near the Militärhistorisches Museum, also located in Gatow. Unfortunately, the airframe is currently in such a sad state that it will probably have to be scrapped.

Into production

Another major milestone was reached on 30 June 2003, when the international type certification for Eurofighter was issued.

Following the seven development aircraft that were all sort of hand-built, five Instrumented Production Aircraft (IPA) were built according production standards on the respective assembly lines, just before full production would start for the four customers. DASA was assigned to build two-seat IPA3 (serialled 98+03) which would perform air-to-air weapon integration trials. IPA3 first flew from Manching on 8 April 2002, piloted by Chris Worning. A few years later, in February 2006, IPA3 would fly with the heaviest load to date: four 1,000lb Paveway IIs, four AIM-120 AMRAAM and two IRIS-T air-to-air missiles, along with three external fuel tanks, resulting in a take-off weight of 24 tons.

Officially, IPA3 was the first Tranche 1 aircraft constructed and delivered. More details on these procurement batches and the acquisition process can be found in that particular section of this report.

The first aircraft destined for the Luftwaffe, dual-seat GT0001 and serialled 98+31 (later to become 30+01), flew almost one year later, on 13 February 2003. It was handed over a few days later, starting its career as a ground instructional airframe with the air force’s technical school at Kaufbeuren. Nevertheless, it was the first German Air Force Eurofighter, kicking off the transition to this modern and capable jet. During the summer of 2003, some more aircraft were delivered and initially remained at Manching for crew training.

All delays encountered, political or not, certainly had an effect on the programme and unit prices, and the fact that four different nations had a say and share in the development and production process can also regarded as less efficient. Still, several certification processes had to be finished to clear the aircraft for its intended roles, but it had come from far. And lets’s face it, Star Wars Episode III (the sixth movie of that sequel– yes it’s confusing for non-fans) had not even reached the theatres in 2003. ■